Youth Justice: current challenges and future directions

Posted by NAYJ on Dec 11, 2024

The NAYJ hosted our annual seminar: ‘Youth Justice: current challenges and future directions’ on 28th November 2024. The event was kindly sponsored and hosted by Lincoln House Chambers, held in Manchester. The seminar brought together youth justice practitioners, students, managers, legal professionals, local government officials and academics from across the country,

A vibrant discussion was fostered by our speakers, including:

- Brenda Campbell KC

- Dr John Wainwright

- Dr Yusef Bakkali

- Professor Hannah Smithson

- Luke Billingham

The speakers brought their diverse lived experiences and academic insights into discussions which considered broader structural issues that interact with the micro-lived realties of children and young people – all exacerbating discriminatory, violent and harmful experiences of children in the youth justice system. This blog addresses three predominant themes discussed throughout the event: ongoing forms of systemic racism; reimagining justice with children; and the importance of relationships with children.

Ongoing forms of systemic racism

Black boys are still overrepresented in youth justice, despite significant reduction in first-time entrants and custodial numbers. Official statistics show a disproportionate representation of black children in the youth justice system, particularly in custody. John Wainwright, a member of the GRaCE project, works with a Peer Action Collective to address racial inequality. John discussed socioeconomic opportunity as whiteness, and invited us to consider an alternative co-created post-colonial world, defined as ‘black space making’, providing black children with valued control over the discourse of their lives. This can allow for the topic of race to ignite interpersonal stories in children and young people’s lives, that could give hope and authentic opportunities to the racial majority in England.

Yusef self-described as an ‘unintentional academic’ from a community seen as a ‘social problem’, shared his explorations on how listening to or creating rap music is being used as evidence against black children in court proceedings. Rap has historically been a form of ‘black art’ yet which has become a form of incrimination. Using social media engagement as ‘evidence’ against some children reflects issues in policing inequality, drawing attention to the role of the police in protecting the status quo within a deeply unequal society. Yusef highlighted that we cannot ‘police away’ underlying social problems.

John and Yusef illustrated how responses to children’s involvement in crime is through colonial ideals of ‘Great Britain’ which points to dysfunctional individuals or communities, rather than addressing the intersection of race and socioeconomic inequality. Luke powerfully illustrated this too, using examples across Paris, London and New York to exemplify an obsession with cultural dysfunction, exploring the ongoing relationship between race, history, culture that permeates through children’s experiences of youth justice.

Re-imagining justice with children in the context of socioeconomic inequality

Luke discussed ‘structural humiliation’ within major cities, including bifurcation of immense wealth but also abject poverty leading to ‘bulimic cities’ that draw people in to ingest wealth then spit them out again into poverty. As Yusef said, inequitable social policies create ‘human debris’ that the criminal justice system hoovers up – professionals are continuously mopping up the mess left behind by education, health care and housing system failures.

The youth justice system suffers from ‘intervenionitis’ – an obsessive faith in the capacity of discrete, bounded interventions to achieve substantial change at the societal level. These interventions may provide easy-to-measure objective outcomes but do very little to address the complexity of harms in children’s lives. Rather than focusing on the provision of criminalising and stigmatising interventions for children’s behaviour that is seen as symptomatic of individual pathology, we need instead to invest in resourcing schools, healthcare, and local communities to address socioeconomic inequality at its roots.

Some positive developments in youth justice were shared, such as a greater focus on diversion, out of court disposals and physical adjustments in courts. However, youth justice academics are failing to re-imagine what justice with children could look like. Despite Child First policy introduced by the YJB in 2021, the experiences of children within the youth justice system, particularly in custody, are still harrowing. Our speakers questioned the limits of Child First, being little more than a ‘badge’ to stick on the current system, and insisted we have a responsibility to re-imagine what youth justice means in the current context of poverty and inequality if we want to strive for significant, whole system change. We must not forget to consistently question the ideological and political position of the criminal justice system.

Importance of relationships

Brenda shared representing a 15-year-old girl charged with murder, yet had never seen a day of safety in her life, mentioning that her legal representative was the nicest anyone had treated her. This demonstrates how both welfare and justice services led to the child feeling abandoned. At the same time, this example highlights the importance of consistent, reliable and caring relationships - increasing feelings of safety, belonging and mattering for children and young people. The provision of intermediaries can be hugely beneficial for children in court, who need the physical presence of a trusted adult who can be in their corner and assist them. Also the interactions with trusted adults can saturate children’s worlds and be a good mechanism for crime prevention.

Luke provided a note of caution: youth workers, or youth justice practitioners are seen as ‘youth whisperers’ (akin to ‘horse whisperers’), who somehow have an innate ability to communicate with children, with no need for organisational support. Systemic issues in organisations need to change to ensure frontline workers have the headspace to achieve the level of attunement they need to work with the individual child. Hannah discussed that children in the youth justice system must keep re-telling their experience of significant trauma to multiple agencies, such that they feel there is a ‘paper version’ of themselves. Children want a constant person to support and advocate for them; someone who knows the ‘real’ them. There needs to be consistency in relationships, expanded beyond youth justice interventions. For all the models and interventions that are constructed and delivered, it is the relationships that matter.

What next for youth justice?

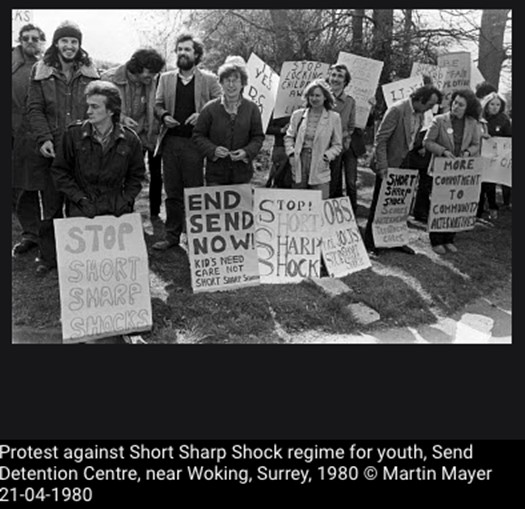

Former Chair of the NAYJ, Tim Bateman, reminded us of the 1980s ‘short, sharp, shock’ era, where adults protested against children being sent to a YOI in Surrey, taking bold, visible direct action through creating road blocks. Perhaps a return to bold radical activism may provide one way of challenging government policy. Certainly, feelings expressed during our seminar demonstrated there are many people passionate about challenging youth (in)justice.

(Youth Detention 1983 (reportdigital.co.uk)

(Youth Detention 1983 (reportdigital.co.uk)

The future direction of youth justice was clear from the collective voice at our annual seminar – one that is radically committed to children’s human rights and addressing social justice, that promotes a system that priorities relationships and fully addresses the complexity of harm injected into children’s lived experiences of socioeconomic inequality and racial injustice. It was evident attendees at our seminar hoped for a more radical response from the new government. However, while we still don’t fully know ‘what’s next’ in the current political climate, we do know that the NAYJ can be voice of the collective who are campaigning for better treatment of children in the youth justice system and beyond. If you are interested in becoming a member of NAYJ, please join us.